Events – Technical/Archive – Rover 6HP Register – Car/Owner Profiles

The family’s Rover 6hp, having just been hand-started in front of 2 new mother in laws and 120 wedding guests outside Elmbridge Church, takes the happy couple David and Libby Timmis on their first married journey – about half a mile to the wedding reception

This section is about the surviving Rover 6hp cars and their present day owners. To kick things off, here is Robin Wilson’s story of the car he has had since buying it by mistake at an auction in 1986

When all else fails, cast a new one – then six more !

The story of how a chance encounter at the 2006 Beaulieu Autojumble finally ended Robin Wilson’s 15 year search for the essential ingredients he needed to cast a new engine block for his 1906 Rover 6hp.

Alternatively:

Mass Production of Rover Engines finally concludes January 2008 – in a shed in Brierley Hill.

They say a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. How true. And if that chain is a 90 year old car, it doesn’t need a lot of links to be complete: just 4 wheels, a seat, an engine, transmission, axles and steering gear, held together with a very rudimentary chassis made of 2×2 ash frame with steel plate reinforcements here and there. No need for doors, wipers, roof, instruments, heater or other such luxuries.

Such was the appeal of the antique looking veteran car for sale at auction back in 1986 that, instead of buying the little red J40 pedal car for my 15 month old daughter that we’d gone to the auction for in the first place, my wife Cheryl and I came away with this charming, and almost as little, green Rover car, an Edwardian 2 seater runabout with wooden wheels and nickel plated oil lamps. It was complete but a non-runner and looked like it hadn’t be running for at least 10 years. It had an Irish registration which the buyer was not entitled to. No problem. It just needed a few mechanical jobs doing, including making a better job of repairing an obvious crack in the engine’s water jacket which had been given a rather shoddy riveted copper plate treatment many years before and was now corroded bright turquoise. Mechanical jobs are the easy ones, what mattered to me was the coach-like wood and metal bodywork – and that was excellent! Such was the optimism as we trailered it home the next day; I even had thoughts of mounting a child seat on it and pottering along the lanes next summer with my toddler daughter Libby enjoying the warm 20 mph breeze on her rosy little cheeks.

Robin, Cheryl and baby Libby Wilson with the “just purchased” Rover 6hp (1986)

The story now goes right back to the 1930’s, in County Wicklow, Ireland. The skeleton of an old fashioned car lies crumbling in the back of a farmer’s shed, a car that he was probably driving from before the outbreak of war, till well past its conclusion on Armistice Day 1918. Maybe the back axle had worn out, second gear had become difficult to engage – and the new Austin Sevens were everywhere now, they could seat 4 people and had a roof and doors and were very good value. So the old Rover was just left there, year after year including one very cold winter when the coolant water froze solid inside the engine. The resident woodworm colony had unanimously decided that ash was tastier than oak. Then in 1938 a young garage proprietor from County Kildare hears about the abandoned old crock in a shed and buys it for a sixpence. He takes it to his garage, does enough to get it running and finds water pouring out of a large crack in the cast iron engine block. He takes it to the local blacksmith, who repairs it with the usual method of copper plate and rivets.

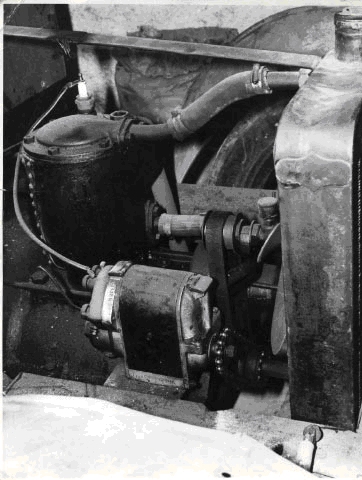

Photographed in Ireland c 1950, note rivet plate repair on back of block

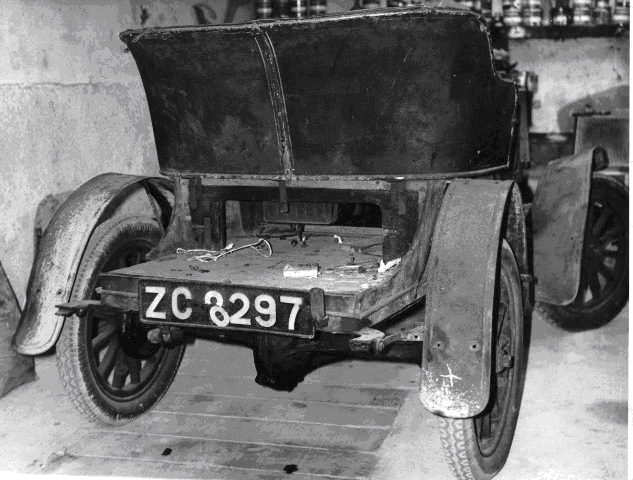

The car now runs, though needs the radiator topping up every day and sends a curious white smoke out of the exhaust pipe. The car is very slow and he only takes it out on short trips for fun, but one day he is told by the Garda that he really should have it registered, so he duly applies to Dublin and gets the registration number ZC 8297.

Photographed in Ireland c 1950, possibly still with its original bodywork

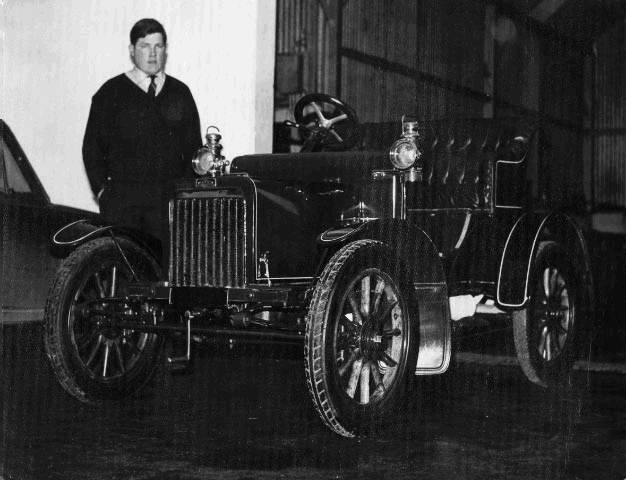

The continuing World War II and other distractions put the little 6hp Rover back into storage for another 25 years or so, till in 1968 he asks a friend to restore it properly, with a re-upholstered leather seat, new black mudguards and the new wooden bodywork to be painted green, then finished with white coaching-lines. The friend’s son poses by the smartly restored Rover for a photograph.

The restored car in County Kildare, Ireland, 1968

The smart and shiny little car is again driven around occasionally, but it seems slower than ever and has an 8hp Rover from 1907 as its stable mate, which is much faster and gets all the attention. By the mid 80’s the 8hp has moved away and the now retired owner decides the time has finally come for his little old 6hp from Wicklow to be auctioned off. So it goes to England, where he’s told there’s a better chance of finding a buyer for an 80 year old car that doesn’t quite run …..

July 1986: The Rover is trailered home from the auction the next day

This brings the story to late 1986, when I as the proud (stupid?) new owner of the little Rover, set to work on “fettling” the curious new old toy. New in the sense that Edwardian technology was new to me, being some 40 years older than anything I’d worked on before. The boiler-like riveted copper plate repair was removed and the crack soon sorted out properly with the aid of a cast iron welding specialist. The chassis was stripped and re-fettled and a few other bits and pieces done including a new brass header tank for the radiator. A rear wheel was showing advanced stages of woodworm in one of the ash felloes, though the oak spokes all seemed OK. So a new felloe was made from laminated ash strips, bent into a half circle and matched to the surviving one, then the whole wheel re-assembled to the old hub and spokes before fitting the red hot steel rim back over the wetted wooden assembly. This is one of those “hope and pray” jobs you have to do boldly in one quick and steamy operation.

Libby with younger brother Edward help Dad clean the wheels

The “Wicklow Woodworm” had preferred the ash felloe to the oak spokes

Finally, on a sunny spring morning in early ‘88 with new petrol in the tank and a battery and modern ignition coil temporarily fitted for the occasion, I’ll never forget the anticipation as I started cranking it over for the first time, ready for the off ! But then, before it had a chance to fire up, I started to hear strange and ominous gurgling sounds in the top of the radiator and began to wonder if all might not be well. Had I missed something or left a pipe loose somewhere? Was the rebuilt radiator at fault? Every time it came on to the compression stroke, it would go “burble burble burble”. Not good. Would we get it on the road that summer after all? Would Libby have to wait another year before her first trip in our antique little Rover?

A previously unseen crack in the wall of the cylinder bore was the problem and with the “blind” bore design of these early Rover engines (there’s no detachable cylinder head) it proved impossible to repair properly, in spite of the application of various techniques over the next few years including more fusion welding, cold stitching and cylinder lining. Water additives were out of the question, this was a leak through the cylinder wall, even Radweld would have no chance against the 50 psi this little 750cc single could muster at TDC! The replacement item was no longer available from my local Rover dealer Parts Department (I’d missed the last of those by about 90 years) and the last used “spare” 6hp block had just been sold to Coventry Museum for their car – I discovered that I’d missed that one by a mere 7 weeks. So we were completely stuck, with a cracked and irreparable engine block and no spares anywhere. This was without doubt “The Weakest Link”. My car was broken and couldn’t be fixed. To cut a long story short, due to this weak link, the car was to remain a non-runner for the next decade and more, making occasional excursions into the garden on sunny days.

If you make your own car noises and push, it’s almost a real car (1991)

Only when I’d summoned the courage (and money) to embark on having a new block made, did things start to happen. Libby was already 17 and having proper driving lessons by then !

While looking around for possible pattern makers and iron foundries, I also started to do some searching of the archives (Veteran Car Club, RSR and other sources) to get in touch with other 6hp Rover owners, in case they needed a new one, or by chance, had a spare block they would let me have. If enough owners could be found and if a few of them wanted a new block, it would be worth producing a small batch and hopefully I could recoup some of the tooling costs. At this stage (2002) there were thought to be about 14 such cars still surviving, most in the UK, though I had only ever seen one other in use and the yellow one at Heritage. Through friends in the Morgan 3-wheeler club I made contact with a pattern maker in Doncaster who was “in production” for new barrels for single and twin engines dating from the 20’s and 30’s. He looked suspiciously at the Rover block: “Never seen anything like this one before”, punctuated by long slow intake of ice-cold Yorkshire air (they say it can get to minus 30 degrees there, up north of the M 18). “Hmmm, tricky little one this …. but I suppose we can have a go ….. won’t be very quick mind you” he concluded, looking at me with a knowing smile, then again at the block for a closer look, as his warm breath thawed a little patch in the ice that had already formed on the surface of this 96 year old lump of cast iron.

Fellow 6hp owner David Bliss then kindly donated a very rusty and broken Rover 6hp engine block (farmyard find, literally) and this was sectioned (as I probably should have been!) to aid the pattern making process. The headless block design has some awkward, totally hidden cooling passageways around the valve ports which cannot be seen and replicated without cutting the block open, so this donation was to become one of the vital ingredients for the project, as it allowed my original block to stay in tact for various other duties, including being the dimensional reference piece for the later machining work on the new castings. An excellent machine shop was found in Brierley Hill and quotations prepared for machining the castings based on a batch of one, possibly extending to 2 or 3, if other owners could be found wanting. For me this little negotiation was an entirely new way of doing business with suppliers, compared to what I’d experienced in Chassis Engineering at Austin Rover, dealing with production volumes of tens or hundreds of thousands of components per year. I guess the buyers at Morgan Cars must feel a bit the same way when they walk in to see a supplier who has just had the Ford people in to negotiate component and tooling costs for the next generation of Fiestas!

Unfortunately, the summer of 2004 came and went and the pattern making had only just started by year end. My engine block had been “borrowed back” from Doncaster to allow the car to get to Ragley Hall in July of that year for the official Rover Centenary. It could be made to run, just, but without much compression and with only a little water in the radiator, otherwise it would impersonate a Stanley steam car for 10 seconds before spluttering to a wet-plug halt in a cloud of steamy and oily exhaust smoke. On a brighter note, the little bit of research that had started out as a quest for engine blocks, for sale or wanted, soon turned into an e-mail enabled, self propelled world wide network and by early 2006 “The Rover 6hp Register” was firmly established with first-hand evidence of 25 surviving cars, of which at least 15 were runners. To my surprise, half of all these were located in Australia or New Zealand.

Rover 6hp Centenary Event, July 2006, Worcestershire

By mid 2006, with the Rover 6hp Centenary celebration event planned (see Freewheel No 318, Aug 06, centre pages), the car was ready with its MOT and age-related registration (BS 9980) and now the patterns and cores for casting the new block were finally made. Then disaster struck. We fell into serious difficulties at the foundry in Sheffield with the casting process itself – as the molten metal went in, the mould kept blowing, each one a total scrapper, thrown back into the furnace before even the patternmaker could inspect it to work out what was going wrong. How frustrating! By now I’d missed the chance to get the new block done and fitted ready for the event. So, a week before our centenary event I again went to Yorkshire and got my block back and refitted, but this time after running it round the garden a couple of times it really took umbrage at being run without enough water, the crack must have got even bigger and the compression was all gone. Still determined that it should participate in the event, at least in the gymkhana on the Saturday, and in sheer desperation on the Friday night to get it running in some fashion, I attempted what must be the ultimate “bodge job” to restore some compression in a cylinder block. Better than Barrs leak seal. No welding required. Simply drain out all the water, remove water cover top plate, blow dry the rusty water cavity and liberally inject that clever new DIY Expanding Foam stuff, as deep as possible into the entire water jacket around the cylinder. Wipe off excess and serve warm, but not too hot. Consume in short doses. Hey Presto !

There was definitely some resistance (compression) when cranking it over on Saturday morning and it then fired up easily. It completed the gymkhana event in good time and with no penalties, both for me and the other driver who competed in it, or should I say on it? That other driver, unaware of the rather unusual coolant material being used under the bonnet, was no less than RSR Hon Chairman Mr Mike Maher! (bet he’s never driven a bodge job like that one before !!!). The car’s 100th Birthday was duly celebrated at the close of the event.

RSR Chairman Mike Maher on Robin’s car doing well in the autotest.

Roll on to September and the Beaulieu Autojumble, a place which is so big and sprawling that you simply can’t get round all the stalls in one day. You either have to be very focused and look only for the specific items you want, going on to the next stall quickly if what you want isn’t obviously visible, or you relax and let yourself sink into the so-called “Beaulieu Blues” and, let’s be honest, just end up wandering from stall to stall in a vintage daze. Anyhow, in a not very focused state of mind towards the end of a long, hot day I suddenly found myself face to face with a pair of brand new Rover-like cylinder block castings. Could they be real, or was I actually hallucinating? The rather tall bloke behind the counter must have thought I was “on something” as I blinked and peered ever closer and then started pinching myself. After a few moments I regained consciousness and realised they weren’t quite the right shape at the top, so asked him what they were for. “De-Dion 6 and 8 horsepower, early 1900s” came the friendly and authoritative reply. I was at the De-Dion Bouton Club stand and here at last had found another vital ingredient in my Rover block making recipe – someone with recent experience and success in making a very similar shaped casting.

I then started to recount all the casting problems we’d been having and describing the various issues with gassing, blow-outs, pre-stoving, cross drilling and generally getting nowhere, with a big foundry place that didn’t seem to care at all. He simply said “been there, done that, wasted loads of time and money – then we discovered a small foundry in Wales who told use to try a certain core maker in Leicestershire and within a couple of weeks we had made a batch of 20 perfect castings, including these 2 you see in front of you”. They say you can just very occasionally make a truly miraculous discovery at Beaulieu and well, for me, this “find” was it!

Memento from the chance encounter with De Dion casting expert

With grateful thanks to the De Dion club and clutching the all-important names and phone numbers, I left the autojumble and just 2 days later made what was to be a final trip to Doncaster, settled the account and put all the patterns, core boxes and rusty bits of sectioned casting in the car to take home.

Mould and Core Boxes in Doncaster, ready to go south

En route I dropped the core boxes off in Leicestershire for a batch of 10 cores to be made using the high tech process which had been the real breakthrough for my De Dion counterpart. A week later the cores and casting boxes were at the specialist foundry on the Gower, where they say the sea air has the perfect blend of trace elements and this ensures the very highest quality of sand casting possible in the UK!

The foundry owner and his right hand man set to work on preparations and just 3 weeks later I had my first good casting done. Eureka ! It was then machined up using measurements off my original block, the bore honed to suit the new piston I’d had made and finally on December 23rd the new block was collected and fitted to the car. Later that same day, in spite of heavy winter fog, the little Rover finally drove on the public road with a fully functioning engine and completed, faultlessly, its first 2 miles. These were the first road miles it had done in at least 30 years and most probably its first time running correctly in something more like 80 years.

Eureka ! First new block machined ready for painting and fitting to car, Dec 06

And what about my daughter and her first ride in this car? No need for a child seat any more, she was 21 by now! But a very auspicious thing happened that same day when I got home from that first chilly run around the lanes. Her boyfriend David must have spotted the opportunity to make the best of my joyous mood and said he’d love a trip round the block (no pun intended) in the little Rover, before it got too dark. About a mile from home as we pop-pop-popped along a quiet country lane he suddenly turned towards me and enquired, in a rather earnest tone “Robin, do I have your permission to marry your daughter?”

“He asked me and guess what – I said YES !”

Well, you have to hand it to the lad; his timing for the big question was impeccable! Even if I’d wanted to say no, or do something cruel like saying “I’ll think about it”, I was just too happy all round to do anything other than shout out just what I felt. So he got the answer he wanted, in a matter of yards, probably even before the next “pop” of the single cylinder engine as we were now in 3rd gear, doing a good 20 mph to get home before dark.

With Libby and her fiancé David, Christmas Eve.

Since that memorable occasion just before Christmas 2006, the car has done a number of local trips and events in 2007 including the famous Creepy Crawly Rally for singles and twins, when it did over 90 miles in 2 days. There was a red 8hp Rover on that event, not seen by myself or 8hp enthusiast Kent Robinson before. I recognised the registration number; it was the very same car that the previous owner of my car had owned for many years in the 60’s and 70’s. The 6 and 8hp Rovers had been stable mates in Ireland for decades and here, on my car’s very first official VCC rally, they were to meet up again. Coincidence or what ! And so, with the benefit of some further work done on axle and transmission parts more recently, my little 6hp is all set now for a busy 2008 and I hope many such years ahead.

Boosted by the success with production of my own block, I was at last able to “consider enquiries” for making some more. By March we had firm orders to make a batch of 6. Not a big deal, but when you consider it represented a major spare or replacement part for some 20-25% of the remaining 6hp Rover cars and could allow me to recoup my tooling costs, it seemed a worthwhile thing to do. Scaling up the production rate from 1 to 6 did however reveal a few consistency problems in the casting process and it took us a few more months of experimenting and scrap-making before we got it right. The skill, tenacity and patience of the foundry owner and his right hand man were no doubt another vital ingredient in the success of this project.

By early summer 07 we were able to make the batch of 6 castings and, after taking their place in a 5 month queue at the excellent but very busy machine shop which operates from a shed in a builders yard in Brierley Hill (West Midlands), these new Rover engine blocks were finally machined up and despatched to customers around the world (well, actually in various counties in England, plus one sent to a customer in Australia). By the way, it must be said that a good machine shop with skilled and experienced craftsmen was another essential ingredient to this project’s success; there were several occasions where a less competent outfit could easily have wrecked the castings by not taking due care and failing to think the job through properly. When the batch size is just 6 you can’t afford to make mistakes with the first half dozen !

The last one was duly completed in the new year and so, for a small scale project that took some 5 years from start to finish, during which time the very last Rover car was made just up the road at Longbridge, it would seem appropriate to mark the concluding milestone of this little 6hp engine project with a headline that reads: “Mass Production of Rover Engines finally concludes January 2008 – in a builders yard in Brierley Hill”. Ironic, really, if you imagine the setting back in 1904 when the very first Rover car was produced, its engine too was most probably made in a shed, in a yard – just down the road in Coventry!

Mass Production, or a straight six for the six ?

Robin’s Rover 6hp Engine Block Project 2002-2007

With acknowledgement and thanks to:

- Roland Frayne, Ireland (for the car’s history 1938-86)

- Mike & Paul Cullingworth at MFC Patterns Ltd, Doncaster.

- Bob Haynes (Morgan 3-wheeler Club, for recommending the above)

- David Bliss, Norfolk (for sacrificial engine block)

- John & Paul at Cambrian Castings Ltd, Swansea

- Austin Parkinson (De Dion Club) for recommending Cambrian

- Bill Pindar at CJB Cores Ltd, Market Harborough

- John & Alan at Merlin Engineering, Brierley Hill

- Customers of the 6 new engine blocks, for their faith and patience!

Getting Technical:

Core Making and Casting Techniques, past and present.

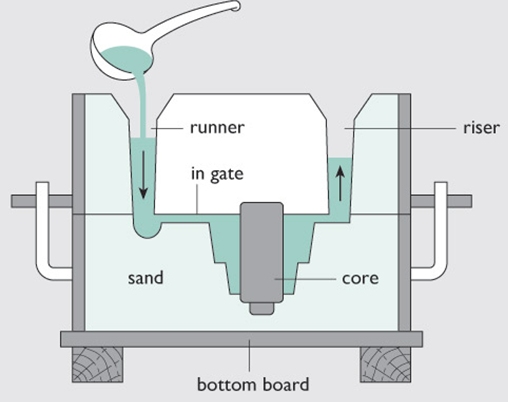

The project to cast a new block for my 6hp Rover engine taught me a lot about the basics of the whole process, bringing to life what you can read a dozen times and still be no wiser about patterns, moulds, cores, runners and risers etc. It also taught me the harsh realities of production defects such as cold shuts, blow-outs, core fractures and all the other ailments that can beset the process.

From the various discussions with experts in the field, chiefly those at Cambrian Castings, I was able to get a very limited insight to a few of the more subtle things about the process, the know-how that is often summed up simply as a “black art”.

For those readers of Freewheel who are interested in elements of this black art, I’ll do my best to take you through the key points, starting with a refresher on the basics of sand casting then going on to the things I found so interesting in this Rover quest. Apologies to any professionals in the casting business (including the Editor) for errors or misrepresentations I have made concerning your most fascinating of art-forms !

Basic Casting Process

Molten iron is poured into a sand mould by means of a tube called the runner and it then fills up all the holes it can find, pushing any air out of the way, then the surplus iron comes out the other end, up the riser, before it all sets solid and you get your iron thingamajig, though it’s best to wait a few hours for it to cool down before sawing off the sticking up bits where the surplus iron came to rest in the runner and riser.

As the molten iron flows in, the glue holding the sand together gets hot and vaporises and mixes with all the air rushing out from all the cavities to make way for the iron. But if all the pockets of hot gas get confused, they try to argue with the iron and try to go back up the wrong way, towards the runner. If all the disobedient gas pockets gang up and have a big argument with the iron and win it, they make the iron stop for a moment as they escape up the wrong way. From nearby the whole thing sounds like a massive burp and if its going to happen, it occurs within a few seconds of the first pouring and is called blow-back, the casting is “blown”. When this happens the iron never completes its proper journey and the whole thing’s obviously scrap. A more annoying defect is when the pockets of gas don’t meet up and don’t confront the incoming iron. Instead they just go for lots of little walkabouts, each negotiating a quiet hiding place somewhere in amongst the molten iron as it sets. Nobody knows this has happened till it’s all over and cooled down. Then if you’re lucky you see all the air pockets looking like aero chocolate and you throw the casting away, after trying to work out why it happened. If you’re unlucky you only discover the problem after spending lots of money machining the casting, when it shows up during the final machining operation as porosity in the finished product, inevitably following Murphy’s Law and positioned somewhere in the casting that really matters, never in a corner where nobody will notice!

The diagram also shows a core. These are required when the thing you want to make is hollow. The core is made a few days before you do the casting and uses a different type of sand which is bonded together then made into the right shape using a core box. No molten iron in this one, just some kind of glue. It may also get baked in an oven to make sure it doesn’t fall apart before the big day. The rather fragile sand core is then carefully placed in the casting box, inside the main sand mould, then you cross your fingers that it doesn’t move as you put the lid on the whole thing ready for casting. You also hope that on the big day when the core has to stand up to the advancing rush of molten iron, that it doesn’t get pushed out of place or broken in half, or let off a whole lot of gas as the glue holding it together suddenly vaporises.

Key Learning Points for casting the Rover 6hp Block

No 1: Make the cores strong enough.

The decision to use a horizontal split line in the mould as per witness marks on the original block, corresponding roughly to the plane of the piston’s top face at tdc, meant that the block had to be cast upside down in order to get the cores to work. So it needed 4 separate cores per block, each one carefully locked into an adjacent one. The core corresponding to the main cylinder bore was very heavy and had to be carried by one of the others, which had a very thin annular section at one point. During casting this sometimes broke and all the other bits ended up in the wrong place, so it had to be thickened up for strength.

No 2: Use a foundry which can explain (or help you diagnose) any problems

First attempts in Sheffield were with ordinary sand/resin mix, hand-packed into the core boxes and left to air-set. When the casting blew, the finger of suspicion was pointed at the cores, though there was no evidence to back this up. The patternmaker’s previous experience was that it can help to pre-stove the cores in an oven, to de-gas them without loosing all the glue. This may have helped, but we still got scrap, the foundry just said they had blown. This routine could have gone on for months; it felt like the blind leading the blindfolded.

3 blocks just cast, but nearest and furthest had blown

No 3: Make cores which don’t gas

Air-set sand cores are known to emit significant quantities of gas, even if pre-stoved. Too much stoving and they fall apart on casting. Too little and they blow. The Rover (and De-Dion) water cooled blind head side valve single is in fact a very complicated casting, with lots of cavities and bottlenecks where the gases can’t escape. Around 1900 when Rover was making these, the black art of casting iron cylinder blocks lay in a number of secrets, including the amount and freshness of horse manure mixed in with the damp (green) sand. (This is not hearsay, it’s true, I have it on good authority from John at Cambrian Castings, whose late father had no less than 68 years experience in the foundry business around London and Essex. Luckily, all this huge wealth of knowledge was able to be passed successfully from father to son, to the benefit of customers like myself). I learnt that the recent De Dion experience with blow-outs and porosity all pointed to this same problem of gassing, that’s why John advised them to get their cores made at CJB in Leicestershire. Here they use the comparatively high tech “Cold Box” method, in which silica sand is mixed with 0.8% resin and catalyst then injected into the core boxes under 60 psi air pressure to get high density and complete cavity fill. It’s then set with amine gas and the air evacuated, producing strong, high quality cores that have a shelf life of several weeks and emit a more controlled and much reduced volume of gas during casting.

Cooled but faulty, the 1 runner and 2 risers remain attached

No 4: Listen to the Foundryman

The final breakthrough that gave us consistent casting quality was when Paul, the supervising foundryman at Cambrian who had personally assembled the Rover cores and moulds on each occasion, had seen something in some of the finished castings which led him to believe one area was at risk of cold shuts, a defect where the iron flow starts to slow down and solidify too early, leaving a ripple on the surface and potentially some local weakness. It also makes the casting more prone to blow. He’d wanted to alter the position of the runner some time before, bringing the entry point closer to a wider part of the cavity to improve flow. But he’d not been sure and, as we’d had some good castings already, didn’t want to risk introducing another failure mode. However, a succession of bad castings then persuaded him to make the change and immediately the problem was cured and the final batch produced without fault.

If I was doing this again (which I don’t have any intention of doing, not even for the few 8hp Rovers I believe are stranded with broken engines) I would make sure the foundry and patternmaker were selected and had got together to finalise and agree the configuration of the moulds and cores and details of the runners and risers etc, before starting to make anything. Hindsight is a wonderful thing !

Carefully pouring and with revised runner detail we’ve now got it sorted.

Note furnace and crucible with half a ton of molten iron in background.

Final Thought: Don’t ever try to make a Business out of This !

Business Reality No 1: Specifications and Costs

The patterns were based on my car’s 1906 block, with the exception of reinforced web sections between cylinder barrel and outer jacket as seen on the 1907 sectioned block and assumed to be an evolutionary Rover improvement made at that time. The need to reinforce the main supporting core meant that we had to deviate from the original flange detail and add thickness to the core section at four points around the periphery of the water jacket. Four “scallops” can be seen where there is reduced metal land width on the top flange. This does not affect the strength or function of the block and cannot be seen when the top cover plate is fitted. The dimensions of today’s valve seat cutting tools forced us to enlarge the blanking plug (access hole) diameter by 1 mm and meant that a pair of new blanking plugs had to be supplied for each block. Other than these minor deviations, the geometry of the 2008 blocks is believed to be an exact replica of the original Rover item from 100 years earlier. After machining, each block was leak tested (by pressurising the entire cooling jacket and passageways to 40 psi) then final honing of the cylinder bore to complete the job.

The castings were made of Grade 17 Grey Iron, a commonly used spec well suited to engine blocks and having good machining qualities. The bore was machined to the 1905-7 bore of 95mm and includes sufficient wall thickness to accommodate the 1908 upgrade to 97mm. To ensure concentricity of bore to cylinder wall thickness, (remember it’s an integrated cylinder head, the bore is blind) the machine shop took special steps to set up the bore machining centreline to be concentric with the actual as-cast outer surface of the top of the cylinder wall. This ensured consistent and maximum wall thickness and would enable the customer to bore out to 97mm, the performance upgrade introduced by Rover in 1907, if so desired. This apparently increases top speed from 25 to 27 mph! There is no evidence in the Rover Brochure that upgraded brakes or aerodynamic stability devices were also being offered at that time.

Business Realty No 2: Allow for high failure rate for the first 10 castings

The blocks were offered as cast or fully machined. In the end all the customers decided to go for the fully machined option. It didn’t make much difference to me.

The fully machined blocks were priced at a very reasonable (in fact very charitable) £1540, this included a necessary and pre-agreed increase mid 2007 to offset unexpected casting scrap costs which the foundry was not prepared to absorb, plus the cost of machining up new blanking plugs. It also included a £250 contribution to the original tooling cost, which was £1500 for the patterns, core and mould boxes. Each good casting plus core set cost £300 and machining was £750 per block. These were the direct costs and against those it approximated to break-even for the 6 sold units.

Increased machine shop costs were incurred on the first (my own) block, done in 2006 before the other 6 were even ordered, as the lessons were learned rather slowly the first time round, on how to set it up and make sure everything was concentric to the casting and square etc. All these set-up costs, including the many phone calls and journeys around the country until the final solution was found late in 2006, were at my own expense and not recovered in the price of the subsequent orders.

Business Reality No 3: Small Potential Customer Base means Very Small Business

The project has been an amazing and rewarding experience for me, though not without its fair share of frustrations and general hassle. It has allowed me to transform my own car from a static exhibit to a reliable VCC (and RSR) rally car and it is my hope that a number of 6hp Rovers will able to continue running for at least another century, thanks in part to this new “limited edition” generation of engine blocks. In the event that another Rover 6hp owner decides in the near future that they need a new engine block, all I would say is that I’d need some time to consider it and the unit price would be at least £2000 !!!

The reality of the project is that it was driven by a personal quest to get my dear old car going properly, whatever it took. The opportunity to find some more customers led me to make a small batch of 6 more blocks, at considerable cost in terms of time and general hassle, above and beyond what it took to get my own first-off block casting made, machined up and fitted.

Business (Car Club) Reality No 4: The RSR pulls Like-minded People Together

Regardless of the business aspects of this project, what for me turned out to be the biggest and I expect most enduring spin-off from this endeavour is the network of fellow Rover 6hp owners which was built up very quickly in under 2 years, motivated initially by me wanting to find some potential customers for a new block, but ending up as a quest to track down and put on the Register all the remaining 6hp Rovers on this planet – along with their current owners. The RSR-supported 6hp Centenary Event in July 2006 was the first time in probably 90 years that more than 3 of these cars (and their owners) had ever got together. These and many of the other 6hp owners on the Register have since corresponded and met and done events together.

The Rover Sports Register has, in my opinion, provided a far more effective club in bringing these rather unloved little cars (and their owners) together, compared to the Veteran Car Club, which is friendly enough but tends to be dominated by the very expensive pre 1905 cars eligible for the Brighton Run. And where are the owners of all those big and powerful Rover 8hp (single cylinder models 1904-1911) hiding now? Come and race the 6hp boys, or at least emulate your colleague Kent Robinson and get writing to the Freewheel editor !

Unexpected reunion: The 6 and 8hp Rovers meet again on the 2007 Creepy Crawly Rally, Windsor.

From c1960 to c1980 these actual cars both belonged to the same owner in Ireland.